We have all heard of ‘rising damp’. Frequently, when people see moisture in the walls of buildings, they will assume that this is what it is, and that costly remedies will be involved. These remedies often take the form of injected chemical DPCs that aren’t always needed – although one should beware of the growing misconception that chemical DPCs are never needed.

The truth of the matter is that rising damp itself is less common than you might think; the presence of moisture is often more likely to have another cause or causes. The purpose of this page is to examine the various types of damp that occur in buildings, their causes and thereby their remedies. Please note that this is not meant to be in any way exhaustive on the subject – whole books have been written about damp, and we doubt that anyone would want to read that amount of detail here.

Put simply, there are three main types of damp that appear in buildings, houses most of all. These are:

Let’s look at each of these briefly in turn, along with their causes and remedies:

Rising Damp

Rising damp is the blanket term generally applied to moisture rising vertically through a wall as a result of naturally-occurring ground water in the soil being soaked up by the wall. Bricks are porous things, and so will act like a sponge when the lower part of a brick is wet. As there is a limit to the capillary action of a brick wall, rising damp will generally only be present to the lower 500 – 1000mm of a wall. And it takes quite a lot of water rising up the wall to create a damp problem that is noticeable and problematic.

Causes of Rising Damp

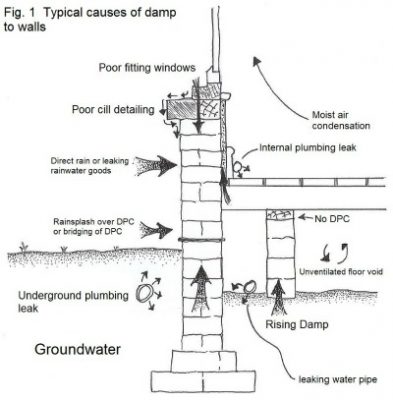

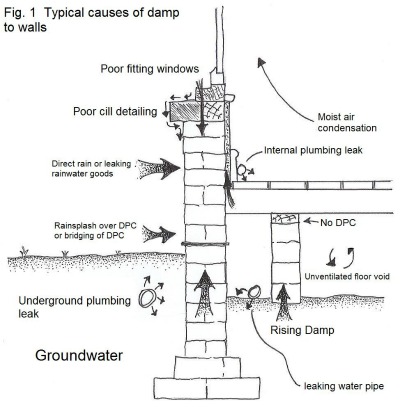

Quite often, when we see damp rising up a wall the cause can be determined without the need for any major remedial works. For example, if paving has been laid up to the foot of the wall, any rain falling on the paving will splash back up and onto the wall above the level of the DPC. This may sound a little far-fetched as a cause of damp, but it really does happen.

Similarly, if the DPC is covered by paving, soil from flower beds, or render, then we will see damp penetrating the wall and moving upwards. All of these are easily resolved without doing anything to the wall itself; moving the soil away from the wall, cutting back the paving by a few inches, or hacking off the render at and below the level of the DPC will serve to remedy the problem.

Figure 1 also shows another culprit – the leaking underground pipe or drain. Clearly, diagnosing and fixing this is a rather more involved job; but again, once the pipe or drain has been mended then the damp issue will not get any worse.

Finally, another problem not shown on the diagram is debris in the wall cavity. When the wall is built, rubble and debris can fall into the cavity and act as a conduit for moisture to pass from the outer leaf to the inner leaf of the wall. This can be diagnosed in a variety of ways, although by far the best is the use of a boroscope – a fibre-optic device rather like an endoscope that can be passed through a hole drilled in the wall. The drawback of this method is that if cavity wall insulation has been installed, an inspection of the cavity in this way becomes impossible.

However, there are occasions when rising damp is just that; the DPC was not installed or has failed. It may be that non-porous engineering bricks (which can be recognised by their characteristic blue colour) were used as a DPC, which simply allows moisture to travel up through the mortar. Whatever the situation, a DPC often has to be installed in order to remedy the problem, although we believe that this should only be carried out as a last recourse.

Before we leave the subject of rising damp, we offer a caution:There has been a large degree of credence given in recent years to the assertion that chemical DPCs are at best an expensive waste of money and at worst an outright fraud. This is not true.It is true that there are and have been firms out there who will recommend the installation of a chemical or other form of inserted DPC unnecessarily simply so that they may do the work themselves. Sadly, this is common in many industries, so if you are recommended to use an expensive solution the first thing you must do isget a second opinion.

However, it is equally untrue that there is no such thing as rising damp, or that the insertion of a DPC is never warranted. There are cases where it is the only practical solution, and is one that genuinely works.

Penetrating Damp

As the name suggests, penetrating damp is moisture passing through a wall. There might be a large number of causes, and these can often be quite obvious. The most common cause, though, is rain or faulty rainwater goods.

So the first step is to check the exterior. As you’d expect, leaking rainwater goods are fairly obvious – damp staining, residue or even moss and algae growth will usually be present. It takes a while for the moisture to penetrate through the wall, so there will invariably be external indications of where the problem is arising.

Poor detailing of the junction of roofs and walls is another cause for penetrating damp. For instance, if where the roof of a single storey rear extension abuts the rear wall of a two-storey house is poorly detailed, we would not be surprised to find signs of damp to the first floor room at the rear. The roof/wall junction will need to be improved to ensure that damp is prevented from building up in the rear wall.

Poor window detailing is also common; a large number of houses will show elevated levels of damp around windows, particularly beneath the window. This may take the form of obvious damp staining, or it may only be discernable with a damp meter. Sometimes such penetrating damp can be remedied very easily with the application of a suitable sealant to the junctions of the window frame and the window opening externally – although there are cases where more detailed work is required.

Condensation

Condensation is the most common cause of damp within buildings. Warm air can hold a far higher quantity of water vapour than cold air; when warm air is cooled, then the water vapour contained in it condenses out. If warm air comes into contact with a cooler surface, then the moisture will condense onto that surface – like breathing onto a mirror.

Cooking and bathing add a lot of moisture to the air within a house, as does exhaled air. Obviously, it would be inconvenient to the occupants to stop cooking, washing and breathing, so we must look to the ventilation of the property to determine why condensation is causing a problem.

Poor ventilation is not at all uncommon, particularly in older houses. When, for example, a Victorian era house was constructed, the source of heating were the fireplaces. Whilst a fireplace is less efficient at heating a room than a modern central heating system, it did offer the advantage that warm, moist air in the house was drawn up through the chimney whenever the fire was lit, and fresh, drier air was then drawn in through small gaps around windows and doors.

As open fires are less common, and old single glazed timber windows have been replaced with modern double glazed units, the moist air inside the house is not drawn out anything like as well, and fresh air cannot enter so easily. We immediately see that condensation will start to be a problem. Add to this the number of modern appliances – cookers, kettles, washing machines and tumble dryers, power showers and so on – that add water vapour to the air and we have a recipe for a very mouldy home.

The importance of mechanical extractor fans in kitchens and bathrooms cannot be understated, therefore. They should be used assiduously, and an adequate over-run should be ensured with bathroom extractors.

Windows made today are required to have built-in trickle vents. These are small ventilation grilles set into the window frames that allow small amounts of fresh air to be drawn in from outside to replace the air removed by extractor fans and the like. Always make sure that they are open; even in winter, the amount of heat lost through them to the outside air is minimal, and they will help to make the atmosphere inside your house much healthier and more bearable.

Voids – for example beneath timber ground floors or in closed up chimney breasts – should always be ventilated. Still air is moist air, and rot flourishes where there are pockets of trapped air. Ensure that all air bricks are unobstructed.

As an aside, one sign that a damp problem is caused by condensation rather than anything else is the presence on the walls and ceilings of pink or black pin mould.

These rarely occur when the damp concerned is rising or penetrating damp, but flourish in a damp atmosphere.

Other Points to Consider

If you have had a problem with damp, and have paid someone to remedy it, do be patient. Whilst the cause of the damp may have been eliminated, it can take as much as one month for each 25mm / 1 inch depth of masonry to dry out. This may mean that if the plaster has been removed from the inside of a wall, you should leave the brickwork bare until the wall has dried out sufficiently – otherwise you will simply be sealing the damp into the brickwork only to find it creeping back out through the fresh plaster.

If an area of wall plaster has become damp or wet, it is best to hack off the existing plaster and apply new. Not only will this help the brickwork dry out, but also the salts contained within the plaster are dissolved by the damp that has so recently entered it. As the moisture evaporates from the surface of the plaster, the dissolved salts are left on the surface. Once the wall has dried out, these surface salts will attract moisture from the air, even through layers of paint, and you may find that irritating damp stain slowly re-appearing. Fresh plaster will prevent this from happening.

We hope that you find this page on damp and its causes useful, although there is much more we could say on the subject. If you have a damp problem in your home, please call us and we shall be happy to advise you.

Pingback: clindamicina en crema para qué sirve

Pingback: buy clenbuterol online